Description

Respecting the slender canon of works from the end of the 13th century, the body of this angel standing with its left knee bent, is marked by a beautiful swaying of the hips which gives it a delicate curve.

Her slightly inclined head is surrounded by hair, held back by a ribbon, and whose pretty curls frame her face. Her youthful face with a small, round chin is marked by tapered almond-shaped eyes stretching towards the temples, a mouth with thin lips and raised corners, sketching a smile full of gaiety.

He is dressed in a tunic, a blouse over a belt tightened at the waist, whose rounded neckline reveals a powerful neck. Long vertical folds mark the bottom of the garment, reaching down to the angel’s bare feet.

He wears a cloak over his sloping shoulders, which he holds with his left arm, causing it to fall like an apron, forming a long, prominent, well-structured flow of folds.

The back of the shoulders features two long, deep mortises intended to accommodate the tenons of large wings, now lost. The top of the skull features a vice hole, common on this type of sculpture.

This angel is undoubtedly part of the group of wooden angels grouped around the two famous Saudemont angels in the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Arras.

It is one of the few examples of these angels being incorporated into altar decorations.

In fact, a fashion in the second half of the 13th century saw a new arrangement appear around altars. On either side of the altar were columns between which were stretched curtain walls. At the top of the columns stood angels similar to the one shown here. This practice was described by Guillaume Durand, Bishop of Mende, in 1286 in his work “Rational des divins offices”.

In addition to their decorative function, the angels also had a symbolic and didactic significance, sometimes carrying candles and liturgical objects, sometimes carrying the instruments of the Passion, and sometimes serving as angel musicians.

Their presence inside religious buildings accompanied a shift in thinking about their nature and role, a major preoccupation of 13th-century theologians. Although they had previously been confined to decorating façades, from the second half of the century onwards, we saw a proliferation of angelic figures, particularly in goldsmith’s and silversmith’s work, but also in stone or wood sculpture, enhanced by rich polychrome and gilding that recalled their supernatural origin.

These altar angels seem to be one of the most characteristic productions of the last third of the 13th century.

The most famous of them, the Smiling Angel of Rheims, has long led historians to believe that this city was the cradle of these angels and their main centre of production, but the texts and works that have come down to us indicate, on the contrary, that production was more widely spread across the northern regions of France, from Artois to Ile de France, from Normandy to Champagne.

Several texts refer to orders placed by the Lords of the region, such as Robert II or Mahaut d’Artois, of whom there are twenty-four in these inventories.

Almost all of them have the same characteristics: an elongated barrel, supple drapery, a long neck supporting a small head adorned with thick curls, outstretched eyes, and an accentuated smile that is both tender and willingly sardonic.

The Angel presented here fits in perfectly with this late 13th century production. It has all the characteristics of this style, and can easily be compared with the works in the Louvre collections (RF 1435).

Its elongated silhouette, the harmonious proportions of the head, the delicacy of the features, the simplicity and fluidity of the drapery make it the archetype of the grace that this highly symbolic production of Gothic art was able to achieve.

Bibliography :

Exposition Paris 1998, L’Art au temps des rois maudits -Philippe le Bel et fil 1285-1328, Galeries nationales du Grand Palais, catalogue, pp 62-711 F.

Baron Françoise, « Lorsque les anges passaient-Décors d’autel aux XIII et XIV siècles » dans L’Estampille-Objet d’art, n323, 1998, p. 62-69.

Le Pogam P-Y, La Sculpture gothique 1140-1430, Hazan, 2020, p. 258-259, 261.

Museo civico di Torino, Intaglio Veneto, Secolo XV

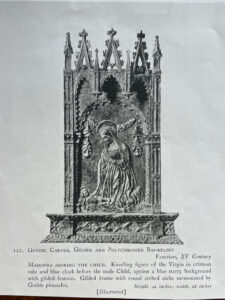

Gothic carved, Gilded and polychromed Bas relief